MIKE BLOOMFIELD BIOGRAPHY

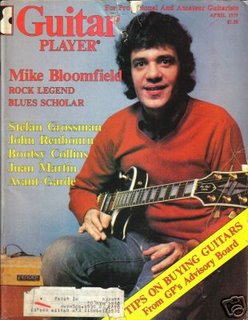

Live fast, die young, leave a great-sounding body of work. It's the stuff musical legends are made of Janis, Jimi, Jim ... and Chicago's own guitar god, Michael Bloomfield, at one time America's answer to Clapton, Page and Beck.

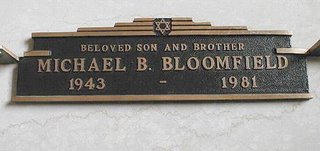

Bloomfield was found dead in his car of a drug overdose at age 36 in San Francisco 25 years ago. In the short version -- woefully inadequate, as all such summaries of a life tend to be -- years of excessive doping and drinking reduced him to a trivia answer.

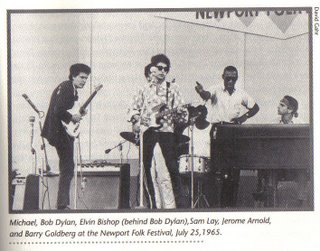

Question: Who played guitar with Bob Dylan at Newport and on the "Highway 61 Revisited" sessions? And even more important in the grand musical scheme: Whose axmanship changed the course of rock 'n' roll by taking electric Chicago blues from the South and West Side clubs to the masses?

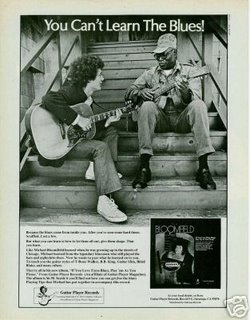

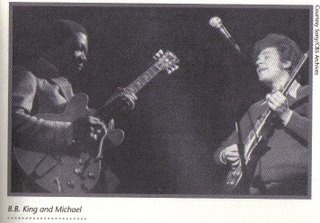

"Some people are just naturals," says blues legend B.B. King, whose success with mainstream audiences stemmed in part from the efforts of Bloomfield and his peers to promote the blues originators. "Mike was a wonderful young man and a great guitarist."

"He touched a chord with a lot of guitarists," explains Allen Bloomfield, the brother 18 months his junior who lovingly oversees the musical estate and monitors the site michaelbloomfield.com "There's a certain passion he evokes and a certain tone that resonates in the hearts in the people. He left a small body of work, but the people who hear it are captivated by it.

He was one of the first to embrace a completely different culture than the one he grew up in. He found an acceptance with [bluesmen such as Muddy Waters and Otis Spann] that he wasn't able to find at home."The myth sometimes is even more romantic than the man himself."It was true of Robert Johnson and true of Bloomfield, kindred blues spirits who each heard the hellhounds on their trail.

Bloomfield was a hyperkinetic, rebellious youth who ran the bustling streets of the city's North Side. Then the Bloomfields relocated to hoity-toity Glencoe, where young Mike never fit in, despite coming from a well-to-do family. He formed various bands during his high school years at New Trier. Guitarist Jim Schwall, a high school classmate who later formed the Siegel-Schwall Band with Corky Siegel, played in one of those early groups."Mike was way ahead of everybody else." Schwall said. "Most of us were involved in the folk revival of the '50s, and when we got bored with that, we found roots music. Mike took a more direct route. He was listening to obscure guys like Smokey Hogg when I met him. I was listening to the acoustic blues players, so having him spin down-home electric blues records was enlightening."

A talent show called Lagniappe hastened the end of Bloomfield's New Trier career. "They told him, 'Under no circumstances can you take an encore,' " Allen recalls. "Of course he took an encore; shortly afterward, he was kicked out. My parents sent him to a private school, the Cornwall Academy, where everybody was a f---up with discipline problems. It was probably there where he first got into dope and other stuff. He was thrown right into the briar patch."That didn't stunt Bloomfield's growth as a guitarist. By the early 1960s, he was ready to strut his stuff before white audiences at the dawn of the North Side blues movement and sit in with postwar Chicago blues kingpins such as Waters and Howlin' Wolf in South Side clubs.

Abe "Little Smokey" Smothers, who was giving guitar lessons to Bloomfield's future bandmate Elvin Bishop, says Bloomfield "learned a whole lot faster than Elvin. Mike was a fast learner. They used to come down to where I was playing at Oakwood and Drexel at the Blue Flame Club. From the Blue Flame, they started going to Pepper's to listen to Muddy."Smothers praises Bloomfield by acknowledging, "He played pretty good for a white boy."

The North Shore millionaire's kid found a running mate in Mississippi-born harmonica ace Charlie Musselwhite, his Near North Side neighbor. Bloomfield had an apartment in Carl Sandburg Village, while Musselwhite and acoustic blues veteran Big Joe Williams rented rooms in back of a record shop."Down the street was a little neighborhood bar named Big John's," Musselwhite recalls. "Over the Fourth of July, they thought it would be nice to have some folk music and asked Joe to play. I played harp with him. They did great business and asked Joe, 'Can you come back tomorrow?' It turned into a regular gig. Mike came down and saw an old upright piano and asked if he could play that. He came back for the next six months. Joe couldn't stay in someplace too long, so he left. Mike and I kept the gig going, and we got a bass player and a drummer."People really responded to live electric blues. We told the owners, 'Why don't you get people like Howlin' Wolf and Muddy Waters?' So on nights we didn't play, they got blues bands from the South Side to come up and play. Other bars saw they were doing great business, and they hired them, too."Bloomfield and Musselwhite moved on to a better-paying gig at Magoo's, and their partner in their nocturnal blues forays, Paul Butterfield, took their place at Big John's.

Butterfield had been playing at Hyde Park sorority parties before landing the North Side gig. The two kept their residency at Magoo's for a year, until their workload -- seven sets a night, from 9 p.m. to 4 a.m. -- became so grueling they gave it up.Meanwhile, in New York, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band landed a deal with Elektra. They were recording while Bloomfield and Musselwhite were in the Big Apple to cut an album for Columbia, and producer Paul Rothchild urged Butterfield to add Bloomfield to the lineup.

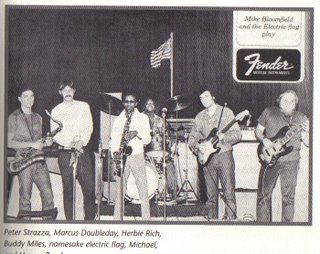

After two Butterfield albums, Bloomfield grew restless. He formed the Electric Flag, promoted by Columbia Records as "an American music band" and as a supergroup with horns. Bloomfield envisioned the group as a Stax-Volt-inspired R&B outfit. The band included his Chicago pals Nick Gravenites on rhythm guitar and vocals and Barry Goldberg on keyboards, as well as Buddy Miles on drums and vocals.

The Flag debuted at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 to overwhelming response, according to Norman Dayron, Bloomfield's producer for nearly 20 years and close friend."I was there in '67, and they weren't talking about Jimi Hendrix or Janis Joplin, they were talking about the Electric Flag," Dayron asserts. "Their performance blew the house down, and everybody was hailing him as the genius of all time."Bloomfield kept the band together for 18 months and one fine album, "A Long Time Comin'." When he began blowing off gigs and finally blew up the original lineup, the Flag did one more LP under Miles' leadership.

Session ace Al Kooper sold Columbia on the "Super Session" jam-record concept as a showcase for Bloomfield's guitar. Then, despite super sales, Bloomfield rejected "Super Session" and the subsequent "Live Adventures" disc as a scam. But Kooper defends those ventures."We had no expectations for sales on this album, and when it dented the Top 10 and outsold Butterfield, the Blues Project [Kooper's answer to the Electric Flag] and the Flag, he was actually embarrassed. The son of a wealthy man, he had turned to the blues world to rebel against his real world. On 'Super Session,' we outsold the blues world, and that surprised both of us."

On 'Live Adventures,' the timing was not great for Michael healthwise and his playing suffered. Another live recording from that time period, from the Fillmore East, went missing for 30 years. As soon as it was located, I went to work on it. Michael's playing is amazing. I released that in 2002 as 'The Lost Concert.' It kind of makes up for 'Live Adventures.' "There are two schools of thought on Bloomfield's last years.

Musselwhite and others believe he became stuck in a creative morass, made worse by drug use and distaste for the "business" end of the music business. A few, including Dayron, think he did some of his finest playing in the '70s for Tacoma and other specialty labels. There's universal agreement, though, that his biggest commercial endeavors of the decade, the Electric Flag reunion of 1974 and MCA Records' 1975 "supergroup," KGB, were ill-advised efforts to cash in on the Bloomfield mystique.

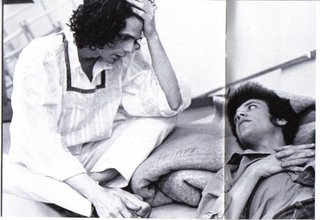

Such commercial projects were painful for Bloomfield."Michael said he had a wire running from ear to ear that would become red hot," Dayron says. "He couldn't hold a band together because his ideas were so revolutionary and so hot. When he got frustrated, he would turn to his favorite thing -- watching the Johnny Carson show. One time he was booked to play for 3,000 people in Vancouver. The Carson show was on the same time, so he didn't go on. Michael walked out, left four guitars behind and checked into a motel that had a TV before flying home."Musselwhite visited Bloomfield a few times at his San Francisco home, "but he'd gotten way off into heroin. It was like he was lost. I remember him saying his dream was to be an English baron with a castle, land and all the heroin he wanted. He might have had some kind of chemical imbalance. One time we drove from New York to Chicago, and all the way he'd be spitting out the car window. When we got back, I saw all the paint had been eaten away on the side of the car from his spitting."Allen Bloomfield maintains that his brother was bipolar, and might have survived had psychiatry known more then about the disorder.

His death on Feb. 15, 1981, saddened but did not surprise his friends. His body was found in his car in a San Francisco neighborhood where one of his heroin connections lived, though he officially died of an overdose of cocaine, a drug he never used. Speculation was that his dealer tried to revive him after a heroin overdose with a shot of cocaine, and when that failed, they dumped his body in the car.

But like Big Joe, Robert and his other heroes, Mike Bloomfield lived and died the life of a real bluesman. And like the great rockers of his generation, he soared musically because he refused to conform to the earthbound notions of the less creatively gifted.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home